The Idea is Not the Hard Part

On Meitheals, Group Projects, and Becoming a Maker

A few years ago, I was in a successful local band. We had fun practicing, wrote original music together, and sang in three part harmony. This made us unique in our hometown scene, which was (as many are) mostly made up of solo guys playing guitar.

I remember wondering why more people didn’t play this way, in bands. To me it was more fun to do and more interesting to listen to than playing solo. I’d grown up going to Irish trad sessions and singing in choirs. It felt natural that music was meant to be played communally.

Around this time, the data was circulating that bands are disappearing from the charts in favor of solo acts. As better production and recording tech became available, artists mostly stopped working together. Why?

In the Irish language communities I follow, the word meitheal has been resurfacing a lot lately. The popularity of the word feels like an expression of our collective yearning for a different way to work together.

A meitheal is a group of people that gets together to accomplish a shared task. It’s the many-hands-make-light-work feeling of a quilting bee, a waulking party, a barn raising, or a group of folks cutting turf or harvesting a crop. It’s a word we don’t have in English, one that feels like an antidote to the kind of hierarchical, status-based, extractive ways of working that we now conflate with work itself.

I do think meitheals are a folk tool that can make our lives better, and writing about it now at Lughnasadh (the kickoff to the co-working party that is harvest season) feels right.

And also…. ugh.

Writing an essay about the joy of work parties and actually working together in groups are… well, let’s say they’re two really different things.

Most folks I know light up at the idea of working in a meitheal.

But be honest. Given the choice between writing a solo essay or suffering through a group project, which do you pick?

There are whole genres dedicated to the drama that happens when people try to work together towards a shared goal. Cheerleader documentaries. HGTV. Every piece of media ever made about Fleetwood Mac. The content is popular because it is so damn relatable.

Dealing with other people is like trying to drink water. Somehow we’ve been doing it every day of our lives, yet still manage to fuck it up pretty often!

I live in a small rural town full of community organizations, and the truth is that the pool of folks who keep the lights on here is pretty small. The same couple clearing knotweed off the walking trail is moving chairs for concerts at the community center. The same retiree helping out at the library is working a shift at the food co-op. The volunteer fire department folks fuel the food pantry.

Having this kind of community means small town drama. It means short tempers and long memories and chaotic politics. It means that plenty of people feel unsafe or unseen, and that plenty leave volunteer projects in frustration, never to return.

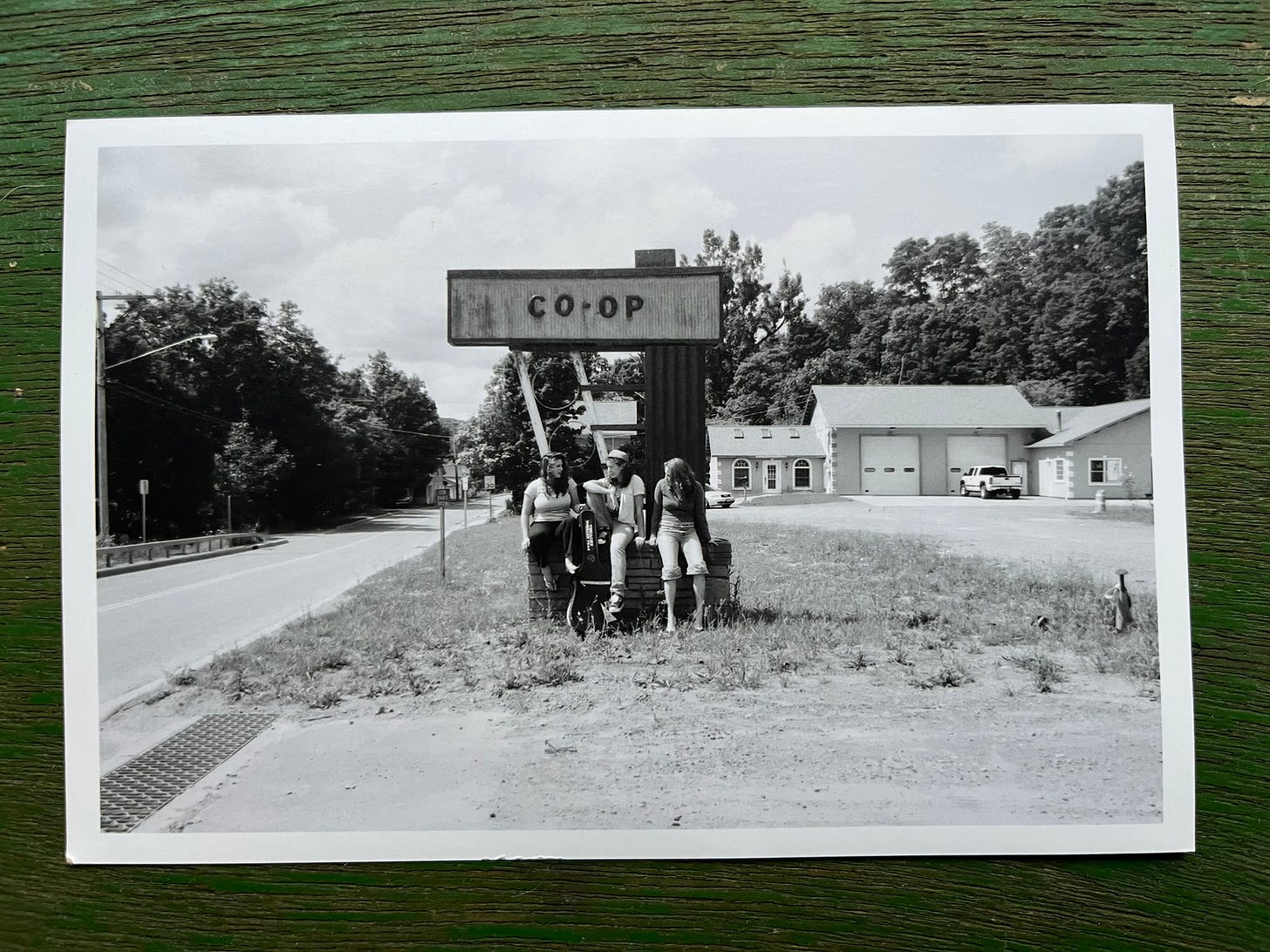

There are splinter groups and petty grudges. There are lots of folks with strong opinions on what should be done and far fewer people who roll up their sleeves to do it. The other day at our new food co-op I was laughing with one of the volunteers about the number of people who come in with their passive “you should reallys” and “have you ever thought abouts.”

I told her about the sign I used to have pinned above my desk at work when I sat at the intersection of six departments and their competing priorities:

The idea is not the hard part.

Because ideas are really only as useful as the actions they inspire.

And what use does the volunteer fire department have for an “ideas guy,” anyway?

When I worked for a fancy story factory in New York, people came out of the woodwork to pitch me their books at cocktail parties. They had great ideas. Bestseller ideas! They just were so busy, they didn’t have the time to sit down and execute them. Someday, someday they would. Or maybe… I would do it for them?

Anyone who has worked in publishing or the arts learns that everyone has a masterpiece stuck inside them. Because all humans are inherently creative.

The internet suggests that we’ll feel better if we buy that next streaming subscription or pants shape or anti-aging cream, but in my experience the only thing that actually calms the howling void is doing a hard and meaningful thing.

I used to think that what set artists apart wasn’t having greatness in them, but the commitment to digging the greatness out. I still think that’s true. But I also think that what gets work stuck in us is rarely about discipline or talent. It’s more about fear.

Because to commit to becoming a maker requires actually facing our grief and disappointment.

When we begin to move from the ether of fantasy to the tangible matter of reality, we risk discovering that we are, in fact, pretty ordinary.

Technology makes all this harder. It’s been a couple of centuries since it felt like a flex to be the best weaver or cobbler or fiddler in any given hamlet. There used to be room for our efforts to feel full of utility and meaning at levels somewhere below the pinnacle of all human achievement.

As a high school ex said about my conservatory audition tape: “It’s not that you’re bad, you’re just no Maria Callas.”

Our ossifying culture of hierarchies and supremacies, winners and losers, tells us that it’s kind of embarrassing to do anything at all if you won’t be able to bodyslam other people with your mastery of it right away. In this way, overconsumption and procrastination and outsourcing our brains to big tech are all self-protective acts.

Because the masterpiece we’ve never begun can remain perfect and unassailable, and if Lady Catherine de Bourgh had ever learned piano, she would be a true proficient.

In the same way, the fantasy version of community and connection that we yearn for can remain free of the injustice and injury and compromise and annoyance and shit work that has plagued group projects since the dawn of time.

The dream that there is a place somewhere out there where we will feel perfectly seen, safe, and supported without a heavy lift of effort remains in the protected realm of disembodied ideas.

Imperfect and ordinary as it was, my July has been full of magical little meitheals that felt better than the brass rings I used to chase after.

The group of musicians who gathered to honor the closing of a local third space. The neighbor who invited me to harvest green walnuts and make nocino in the kitchen with her young niece. The old friend who came to visit and joined me at the co-op to move a chest freezer down the block on a dolly. The wood guy who insisted on helping Rev stack all our wood for the winter. The community theatre troupe that I played music for at a garden party and whose Macbeth we went to see, a family making space for folks to try and fail and learn and grow and connect through art.

Maybe what I’ve been struggling to explain to you here is that everything that sounds annoying and disappointing and bad about Doing Group Projects With Flawed Humans is that… what makes it hard is also what makes it good.

This messy work of learning to lean and be leaned on without creating collapse requires not just thinking about other people as pillars of support, but becoming load bearing ourselves.

And as it is with our bones— which become stronger under pressure but under too much will break— this process requires developing an honest sense of our own capacity. It demands that we build tolerance for acting a little beyond our limits or a little below our desires. We all know a person who holds everyone while withholding their own pain. We all know a person who is willing to inconvenience, but not to be inconvenienced.

You know in your bones whether you’re more prone to spiritual osteoperosis or to repetitive stress fractures. And seeking out meitheals is a helpful way to experiment with distributing that load and practicing that balance.

We don’t have to be good at it right away.

My little band endured for about five years, which was a pretty good run for a group project. During that time there were plenty of struggles and frustrations and there were also moments of hard-won satisfaction and pockets of total joy.

I’m tempted here to gloss over how awful it feels when a communal project like that collapses. But the identity-shaking intensity of losing your place in a group touches our deepest lizard brain and all its gnarly survival wiring.

This is the reason, I think, that bands have been disappearing from the charts in favor of production robots, and why an old-world idea like meitheal never made it into modern English. Our protective fear of rejection and judgment keeps us choosing the ease and comfort and isolation of tech (including syncophantic AI companions) over the connections we claim to want.

The paradox of building connection and trust with other people is in this ancient dance of what we owe one another and what we have capacity to give. How much is too much to ask, or too much to sacrifice? How do we negotiate these strange spaces between me and you, us and them, ideals and realities?

There is no binary answer.

There is only the work, common as mud.

Folkist Practice

Little side quests for folks who want to weave this month’s theme into everyday life. These aren’t affiliate links, just things I want to share!

Is there a project you’re been meaning to do that would be easier with help? Can you make it into a work party?

Maybe loosen up about having people over. I used to not invite folks to my house unless I could welcome them like the prodigal son. (A friend coming to Queens from Brooklyn once texted THERE HAD BETTER NOT BE THREE TYPES OF CAKE WHEN I GET THERE.) Now I’m ok with more casual connection—just some tea and easy snacks like popcorn made in the whirlipop. This weekend it was really nice to have an old friend stay over for a restorative hang that lasted three days.

If you’re more comfortable asking for help than being challenged to stretch your skills, maybe practice doing something that feels beyond your capacity this month. If you’re more comfortable doing something alone than asking for help, maybe practice inviting someone in.

Give a listen to Forsyth, the project of a couple Boston folks I know who are defying the odds and starting a spine-tinglingly good band… in this economy?!

Tine chnámh is the name for the fires we’ll have this weekend to celebrate the shared work of the summer. Bone fire / bonfire. If you have the space, light a campfire and invite some friends. Share the load.

Folkist Work is a slow-pulse monthly newsletter from me, Nora— a haver of day jobs, maker of folk music, do-er of laundry, and founder of the Folkist Space Residency in Upstate New York. I share resources and mini-essays about using our ancestors’ mostly-free, mostly-analog folk practices to endure a difficult world, work for a better one, and make modern life feel worth living again. Like the solar and wind power of your laundry line, this newsletter is always free. If you liked it, I hope you’ll say hi or send it along to a friend.

Love everything about this essay. Thank you for this beautiful piece of writing that names so many of my feelings while challenging my inherent hatred of group projects and reminding me why I keep doing them!